The audacity of the detached manner in which the District Commisioner is able to sum up the tragedy of Okonkwo's fate is only outmatched by that of his plans to chronicle the demise of an entire culture in a single book, which will most likely only include the European perspective on Imperialism. Just as the District Commisioner's lack of familiarity with Okonkwo's life renders him unfit to pronounce an opinion on the man, the Europeans' ignorance of African culture similarly placed them in an inadequate position for judging the African culture as a whole. Yet, for many years, the main account of African history was written by Europeans. Achebe used the irony of the District Commissioner's literary plans to foreshadow the Europeans' subsequent misrepresentation of African history and culture.

By having first shown readers a firsthand glimpse into African society and the life of Okonkwo and his people, Achebe attempts to shed light on the true face of Imperialism. As seen by the court messengers' cruel treatment of Okonkwo and the other clan leaders, the District Commisioner's claim that the Europeans "brought a peaceful administration" (p. 167) is proven false. Readers are able to witness the injustices that took place due to Imperialism instead of being misled into believing claims such as that of the District Commisioner.

Unfortunately, for a considerable time after Europeans had won control of Africa, the actual history of Okonkwo and his people was "buried like a dog" (p. 179) by the proponents of Imperialism.

Angelica's AP response

Wednesday, April 10, 2013

Uchendu On Truth: Ch. 15-16

"There is no story that is not true" (p. 122). These words spoken by Uchendu suggest that there is always some degree of truth in every idea and ideology, even if the whole is not completely correct. Considering Uchendu's appreciation of story-telling as a method of communicating important truths, his open-mindedness towards even seemingly outlandish stories is natural. Although Uchendu's statement may appear to claim that truth is only relative to each culture and people, it is also a fair interpretation to consider his words a testament to the limitations of human understanding.

In this same passage, Uchendu highlights how customs can vary widely from region to region. This observation illustrates how easy it is for the truth to be obscured in the midst of countless and diverse ideologies. Thus, Uchendu is warning his companions not to rashly dismiss a story that sounds strange since even incorrect facts can give the mind clues towards the truth. Later, readers see the conflicts between the Westerners and Africans up close. It is interesting to notice how quickly each side dismisses the other's customs. Such ill-advised behavior brings to mind Uchendu's cautioning, "There is no story that is not true".

Nwoye's conversion to Christianity is an event which seems to substantiate Uchendu's claim. Nwoye embraced the new religion mainly due to the fact that its message of love and mercy resonated with something already within his heart. Most notably, the frustration and despair awakened in Nwoye as a result of his perception of his culture's shocking actions (such as killing Ikemefuna and discarding twins) are appeased by the message of love found in Christianity. Thus, even though Nwoye did not immediately understand Christianity as a whole, he quickly found answers for many of his deepest questions in the strange, new religion.

In this same passage, Uchendu highlights how customs can vary widely from region to region. This observation illustrates how easy it is for the truth to be obscured in the midst of countless and diverse ideologies. Thus, Uchendu is warning his companions not to rashly dismiss a story that sounds strange since even incorrect facts can give the mind clues towards the truth. Later, readers see the conflicts between the Westerners and Africans up close. It is interesting to notice how quickly each side dismisses the other's customs. Such ill-advised behavior brings to mind Uchendu's cautioning, "There is no story that is not true".

Nwoye's conversion to Christianity is an event which seems to substantiate Uchendu's claim. Nwoye embraced the new religion mainly due to the fact that its message of love and mercy resonated with something already within his heart. Most notably, the frustration and despair awakened in Nwoye as a result of his perception of his culture's shocking actions (such as killing Ikemefuna and discarding twins) are appeased by the message of love found in Christianity. Thus, even though Nwoye did not immediately understand Christianity as a whole, he quickly found answers for many of his deepest questions in the strange, new religion.

Take It or Leave It: Mentorship and Wisdom: Ch. 13-14

A respected elder named Ezeudu had warned Okonkwo against taking part in the execution of Ikemefuna since such an action would be akin to a father murdering his own son. Through his warning, Ezeudu displayed his keen wisdom, which enabled him to recognize the negative moral implications of Okonkwo's planned action. Yet, due to his fear of appearing weak, Okonkwo ignores the advice and suffers emotionally for it. Ironically, the fateful incident that leads to the exile of Okonkwo occurs at the funeral Ezeudu. Arguably, Okonkwo's exile is part of his punishment for spilling Ikemefuna's blood.

Once Okonkwo leaves his clan, he arrives at another crossroads at which he can either take the advice of an elder or leave it. This elder, Uchendu, urges Okonkwo to view problems in the larger context of human suffering and, in this way, realize that Okonkwo is not "the greatest sufferer in the world" (p. 117), knowlege that would alleviate the despair Okonkwo experiences during his exile. Uchendu's advice is perfectly suited for Okonkwo since one of Okonkwo's main flaws is his tendency to lose himself in his pursuit of wealth and power. Uchendu is wise in saying that losing wealth and power is a much smaller evil compared to the loss of loved ones. However, Okonkwo once again chooses to reject the advice and, by the end of the novel, has lost all hope.

Once Okonkwo leaves his clan, he arrives at another crossroads at which he can either take the advice of an elder or leave it. This elder, Uchendu, urges Okonkwo to view problems in the larger context of human suffering and, in this way, realize that Okonkwo is not "the greatest sufferer in the world" (p. 117), knowlege that would alleviate the despair Okonkwo experiences during his exile. Uchendu's advice is perfectly suited for Okonkwo since one of Okonkwo's main flaws is his tendency to lose himself in his pursuit of wealth and power. Uchendu is wise in saying that losing wealth and power is a much smaller evil compared to the loss of loved ones. However, Okonkwo once again chooses to reject the advice and, by the end of the novel, has lost all hope.

Women, Ogbanje, and Egwugwu---Ch. 9-10 (Customs of a Culture)

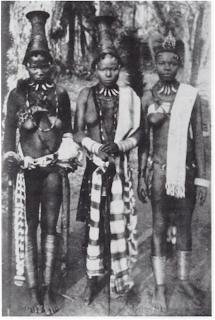

Through Ekwefi's struggles, Achebe draws a parallel between Igbo and European women. Achebe asserts that, regardless of race or culture, all women share certain human experiences such as the agony of losing a child. This fundamental similarity refutes claims of Western novelists, such as Joseph Conrad, who tried to portray African people as unfeeling and primitive.

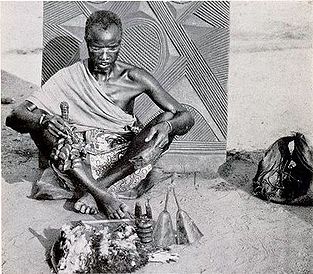

Undoubtedly, the attempts of Ekwefi and Okonkwo to find a way to prevent the frequent deaths of their newborn children do highlight a difference between European and African cultures. Although Ekwefi and Okonkwo seek expert advice just like European families, their expert comes in the form of a medicine man instead of a licensed doctor. It is clear to readers that the Igbo people have as much trust in the medicine man's magic as Europeans place in doctors' scientific knowledge. The medicine man's explanation for the frequent deaths of Ekwefi's children is heavily based on the supernatural beliefs held by the Igbo.

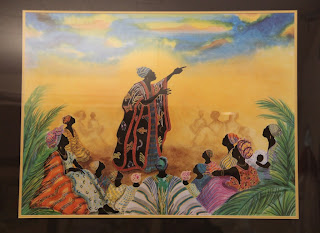

In Chapter 10, readers learn about another important aspect of the Igbo culture: the egwugwu who preside over cases concerning disputes within the clan. Believed to be the spirits of the clan's dead fathers, the egwugwu are highly respected and strike fear into women and children. Indeed, part of the purpose of men taking the role of egwugwu is to preserve the order of the Igbo community, which places women (with exceptions such as priestesses) below men.

Wednesday, April 3, 2013

Even the strongest bow can break--Internal Conflict in Ch. 7 and 8

In comparison, Nyowe's quiet appearance is caused by his inner despair. Achebe states that Nyowe's wound is like "the snapping of a tightened bow" (p. 53). Nyowe had continually sprung back after his father's rebukes, but the blow of his best friend's death, like that of the realization that innocent infants were left to die, leaves an irreparable injury on Nyowe's spirit. Through this simple simile, Achebe is implying that Nyowe cannot recover from the darkness that has fallen over his life.

"Yam, the king of crops"--Family Relationships Ch. 4-6

Okonkwo's main goal is to rise in status as a great man (the opposite of what his father Unoka was) and, consequently, imposes a strict code of discipline on himself and his family in order to achieve his dream. Any affection that dares to well up within Okonkwo's heart, such as his favoritism towards Ikemefuna, is immediately stomped down by Okonkwo, who sees love as weakness. Fittingly, Okonkwo's treasured crop is the yam which the narrator describes as "a very exacting king" who demands "hard work and constant attention" (p. 28). Likewise, Okonkwo expects much from his family as seen in his harsh rebukes of Nwoye and Ikemefuna. Yet, Achebe reveals a flaw in this seemingly ideal Igbo man: Okonkwo easily loses self-control and reason due to his fear of failure. Although Okonkwo wishes to be fearless and strong, he dreads everything that is resonant of the mediocre and reacts as violently as someone with arachnophopia who sees a spider. For example, the narrator notes that "Okonkwo was not the man to stop beating someone half-way through" (p. 25), thus pointing out Okonkwo's lack of self-control, which is the hole in his otherwise solid wall of discipline.

The absence of love in Okonkwo's household is harmful for his wives and children. This is easily discovered since Okonkwo frequently destroys the peace of his home with his angry outbursts which are often accompanied by the beating of one of his wives.

On Achebe's Writing Style, Ch. 1-3

Achebe's style is rich in figurative language and descriptive diction. As I read the first few chapters of Things Fall Apart, I quickly felt transported to the world of Okonkwo and his people by the descriptions of the legendary wrestling match, when "drums beat and the flutes sang and the spectators held their breath" (p. 1). The intensity of the wrestling match is emphasized by this mix of excited sounds and tense silence. Achebe's use of different types of imagery, from auditory to organic, captivates the reader's imagination by appealing to multiple senses. Rhetorical devices such as similes and personification serve to add layers of meaning to the novel. For instance, Achebe attributes the music of the flutes to the instruments' own singing through personification, thus implying the important and familiar role of these instruments in the community's life, almost as if the flutes were also villagers. The parallel structure achieved through the frequent use of "and" to connect short clauses allows Achebe to infuse his novel's narration with a rhythym of its own. The syntax of the narration seems to imitate the poetic speech of the Igbo people. Indeed, the Igbo words neatly inserted into the novel enable readers to connect with the culture featured therein.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)